.jpg) The

sequence of events that ignited the Haymarket bomb consisted of a

tragic combination of intention, accident, and surprise. What transformed

fearful possibility into appalling actuality was an almost palpable sense

that violence was inevitable, and, perhaps to some, even desirable. The

prosecution's questionable accusation of conspiracy notwithstanding, this

mood of expectation made almost everyone even tangentially involved an

unwitting accessory as the drama headed to an explosive climax.

The

sequence of events that ignited the Haymarket bomb consisted of a

tragic combination of intention, accident, and surprise. What transformed

fearful possibility into appalling actuality was an almost palpable sense

that violence was inevitable, and, perhaps to some, even desirable. The

prosecution's questionable accusation of conspiracy notwithstanding, this

mood of expectation made almost everyone even tangentially involved an

unwitting accessory as the drama headed to an explosive climax.

Roots of the Haymarket Meeting

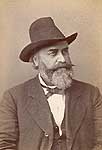

On the afternoon of Monday, May 3, the first working day after the national eight-hour walkout, August Spies was invited to be the German-language speaker at a rally of the striking Lumber Shovers' Union. Coincidentally, the meeting took place very near the main factory of the McCormick Reaper Works, whose union employees had been locked out since February. As Spies spoke, a portion of the crowd broke away to join McCormick strikers in heckling their non-union replacements as the latter left the plant. Spies advised his listeners to exercise restraint, but a melee broke out. When the police arrived, they answered jeers and stones with clubs and guns, killing two workers.

The sounds of this battle drew others from the Lumber Shovers' meeting, including Spies, to the scene. What he saw appalled him. "Well, as a matter of course," Spies recalled at the trial, "my blood was boiling, and I think in that moment I could have done almost anything, seeing men, women and children fired upon, people who were not armed fired upon by policemen." He hastily returned to his office in the Arbeiter-Zeitung building, where he poured his outrage into a deliberately inflammatory bilingual broadside exhorting laborers to stand up like men to their murderous oppressors. He titled this broadside "Workingmen to Arms!", but the person who set the text in type had, without asking Spies, added the heading, in full capitals, "REVENGE."

Later that same evening a

few dozen of the most militant anarchists, including George Engel and

Adolph Fischer, met in Greif's Hall on Lake Street. This was one of a

series of secret sessions, the prosecution would charge, in which the

anarchists plotted how they would attack the police. Many of the key facts

about

why this and other gatherings took place, who was there, and what actually

happened were disputed during the trial. What is not in dispute is that

the news of the riot at the McCormick factory led those who met at Greif's

to decide to hold an outdoor public protest meeting the next evening.

The location the organizers selected for this meeting was the nearby Haymarket,

on Randolph Street just west of Desplaines Street, a few blocks west of

the South Branch of the Chicago River. Fischer agreed to arrange to print

and distribute handbills advertising the meeting and to find the "Good

Speakers" these handbills promised. When he arrived at the Arbeiter-Zeitung

for work the next morning, the first person Fischer invited to speak was

Spies, who had no knowledge of the meeting up to this point.

about

why this and other gatherings took place, who was there, and what actually

happened were disputed during the trial. What is not in dispute is that

the news of the riot at the McCormick factory led those who met at Greif's

to decide to hold an outdoor public protest meeting the next evening.

The location the organizers selected for this meeting was the nearby Haymarket,

on Randolph Street just west of Desplaines Street, a few blocks west of

the South Branch of the Chicago River. Fischer agreed to arrange to print

and distribute handbills advertising the meeting and to find the "Good

Speakers" these handbills promised. When he arrived at the Arbeiter-Zeitung

for work the next morning, the first person Fischer invited to speak was

Spies, who had no knowledge of the meeting up to this point.

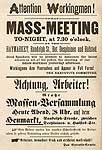

Spies agreed, and he put a notice of the meeting in that day's Arbeiter-Zeitung. When later that morning he saw the newly printed posters with the line, "Workingmen Arm Yourselves and Appear in Full Force," however, he said that he would not speak unless these words were removed. Fischer was summoned down from the composition room on an upper floor, and he conceded to Spies's demand. While virtually all the broadsides that were distributed (about twenty thousand were printed) did not contain the controversial line, a few of the unedited ones did find their way into circulation—and became another piece of the state's evidence.

An Inauspicious Beginning

While the rally was called

for 7:30 p.m., it did not begin until over an hour later. Thinking he

would not be the first person on the program, Spies arrived after eight,

only to find that no other speakers had arrived and that the crowd of

about two to three thousand, which was far smaller than hoped for, was

already  starting

to disperse. Hoping to salvage the evening, Spies tried to manage the

rally as best as he could. He spotted a wagon a half block up Desplaines

Street, and he decided to turn it into a makeshift podium. He made a brief

search for Albert Parsons, whom someone told him was nearby, but Spies

did not find him. He then sent Balthasar Rau to the Arbeiter-Zeitung

building, where Spies knew the American Group was meeting, to see if Rau

could recruit other speakers. Rau was an advertising agent for the Arbeiter-Zeitung,

a stalwart in the International Working People's Association since its

founding at the Pittsburgh Congress in 1883, and a good friend of Spies.

In the meantime, Spies began to address the crowd.

starting

to disperse. Hoping to salvage the evening, Spies tried to manage the

rally as best as he could. He spotted a wagon a half block up Desplaines

Street, and he decided to turn it into a makeshift podium. He made a brief

search for Albert Parsons, whom someone told him was nearby, but Spies

did not find him. He then sent Balthasar Rau to the Arbeiter-Zeitung

building, where Spies knew the American Group was meeting, to see if Rau

could recruit other speakers. Rau was an advertising agent for the Arbeiter-Zeitung,

a stalwart in the International Working People's Association since its

founding at the Pittsburgh Congress in 1883, and a good friend of Spies.

In the meantime, Spies began to address the crowd.

When Rau arrived at the American Group meeting with his message from Spies, Samuel Fielden and Albert Parsons responded that they would speak at the rally. They and other members of the American Group, including Lucy Parsons, headed to the Haymarket on foot. Once they appeared, Spies finished his speech. Parsons and Fielden joined him on the wagon, and first Parsons and then Fielden addressed the crowd.

At the trial the accused cited these logistical details as proof that there had been no bomb plot. They pointed out that although Engel and Fischer had been involved in the planning, the former was at home the entire evening, while the latter left before the bomb was thrown. Michael Schwab was in the area before the rally, but was addressing workers at another meeting several miles away by the time it was in progress. The three speakers—Spies, Parsons, and Fielden—had no role in organizing the event. Parsons and Fielden had scarcely heard about it and had no plans to attend until Rau pressed them into service, after the meeting had already begun. Albert Parsons also pointed out that he and his wife had brought their two young children along, which they would never have done had they expected violence. Oscar Neebe and Louis Lingg, who were nowhere near the Haymarket the entire evening, had no connection to the rally at all. Finally, although Spies, Parsons, Fielden, Schwab, and Neebe had participated in many anarchist activities together, they had serious differences with Fischer and Engel, whom some of them did not know well, and Louis Lingg was virtually a stranger to them.

There is little question,

however, that the authorities were  extremely

concerned that the Haymarket rally might produce serious trouble, planned

or otherwise. With the city so on edge in the wake of the eight-hour demonstrations

and the McCormick riot, with other smaller but still troubling episodes

having occurred that day, and with the newspapers fanning public fears,

Mayor Carter Harrison decided to attend. As he listened to the speakers,

he purposely lit and relit his cigar several times in order to make sure

his presence was known to the speakers and the crowd.

extremely

concerned that the Haymarket rally might produce serious trouble, planned

or otherwise. With the city so on edge in the wake of the eight-hour demonstrations

and the McCormick riot, with other smaller but still troubling episodes

having occurred that day, and with the newspapers fanning public fears,

Mayor Carter Harrison decided to attend. As he listened to the speakers,

he purposely lit and relit his cigar several times in order to make sure

his presence was known to the speakers and the crowd.

Earlier in the day, Inspector John Bonfield ordered lieutenants based in other areas of the city to ready small units of their men for duty in the Desplaines Street Police station, a half block south of Randolph Street and the Haymarket. Throughout the evening Bonfield kept tabs on the meeting through reports from plainclothes policemen who listened to the speakers and watched the crowd. According to Harrison, who was called to testify at the trial by the defense, Bonfield told him of rumors that the Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad freight houses would be blown up since they were filled with scabs, and that the Haymarket rally was just a ruse to distract the police away from an attack on the McCormick works.

The rumors reported by Bonfield were unfounded, but in any case there seemed to be no trouble in the Haymarket. Harrison described the speeches as tame by current standards. The next day's Chicago Tribune, whose reporting of anarchist activities was relentlessly hostile, described Spies's rhetoric as "remarkably mild." Convinced that his presence was no longer required, Harrison left the rally while Parsons was still addressing the crowd. The mayor conferred one more time with Bonfield and set off on foot to his home near Union Park, about fifteen blocks west on Randolph Street. By this time Fielden had begun to speak, but a cold wind from the north and the prospect of rain had done much to diminish the crowd. There was some talk of reconvening in Zepf's Hall at Desplaines and Lake. Parsons, Fischer, and several others made the short walk there while Fielden was still speaking, but the consensus was that the meeting was just about over.

The Bomb

It was about half-past ten,

with only a few hundred spectators remaining, as Fielden told his listeners

that he would be brief. For whatever reason, Bonfield decided to act.

The inspector hurriedly assembled his special force of about 175 men on

Waldo Place, just  south

of the station, and then marched them in formation up Desplaines Street

and through the dwindling crowd to the speakers' wagon. Bonfield's second-in-command,

Captain William Ward, ordered, "In the name of the people of the state

of Illinois," that the meeting disperse "immediately and peaceably." Fielden,

who claimed in his trial testimony that he had less than a minute remaining

in his speech, stated also that he responded "in a very conciliatory tone

of voice," "Why, Captain, this is a peaceable meeting." According to Fielden,

when Ward angrily repeated his order, the anarchist replied, "All right,

we will go," and got down from the wagon.

south

of the station, and then marched them in formation up Desplaines Street

and through the dwindling crowd to the speakers' wagon. Bonfield's second-in-command,

Captain William Ward, ordered, "In the name of the people of the state

of Illinois," that the meeting disperse "immediately and peaceably." Fielden,

who claimed in his trial testimony that he had less than a minute remaining

in his speech, stated also that he responded "in a very conciliatory tone

of voice," "Why, Captain, this is a peaceable meeting." According to Fielden,

when Ward angrily repeated his order, the anarchist replied, "All right,

we will go," and got down from the wagon.

Eyewitnesses disagreed about what happened after Ward repeated his order. But many recalled seeing the "hissing fiend"—a round object with a fiery fuse—as it coursed through the darkness just above the heads of the crowd on the east side of Desplaines Street. The bomb landed in the ranks of the police near the wagon. Carter Harrison could hear the explosion from inside his home.

Shrapnel from the bomb ripped through the body of Officer Matthias (in some sources spelled Mathias) J. Degan, fatally severing a major artery in his left leg. The state's witnesses maintained that the bombing was instantly succeeded (some said preceded) by gunfire from the crowd, and that the police valiantly held their position and returned fire. But the weight of the testimony and evidence suggests that, understandably terrified by the blast, the policemen initiated the gunplay, firing every which way, including into their own ranks. While several of their number besides Degan appear to have been injured by the bomb, most of the casualties seem to have been caused by bullets. About sixty officers were wounded in the riot, as well as an unknown number of civilians. Among the latter were Samuel Fielden and August Spies's brother Henry, who were both hit by gunfire but managed to get away.

Others tried to escape as

quickly as they could, scattering in all directions as the police used

their pistols and clubs indiscriminately. Jammed so tightly together that

they could not run, some huddled in fear against the buildings along Desplaines

Street.

In a few minutes it was all over. The police gathered their wounded and

carried them to an impromptu infirmary in the station house, where they

were attended by several physicians called to deal with the emergency.

In all, seven policemen and at least four workers (there is no accurate

count of the latter) were killed in the riot, though some of the officers

lingered for several days before they passed away. The death of an eighth

policeman two years later was attributed to wounds sustained at Haymarket.

The experience unquestionably altered the lives of many of those who survived.

Several officers suffered amputated limbs, and one lost a section of his

jaw.

Street.

In a few minutes it was all over. The police gathered their wounded and

carried them to an impromptu infirmary in the station house, where they

were attended by several physicians called to deal with the emergency.

In all, seven policemen and at least four workers (there is no accurate

count of the latter) were killed in the riot, though some of the officers

lingered for several days before they passed away. The death of an eighth

policeman two years later was attributed to wounds sustained at Haymarket.

The experience unquestionably altered the lives of many of those who survived.

Several officers suffered amputated limbs, and one lost a section of his

jaw.

The bomb-talking that had suffused anarchist rhetoric had moved to bomb-throwing. In her 1884 "Word to Tramps," Lucy Parsons had urged the desperate not to suffer and die alone but to visit dynamite in the midst of their oppressors. "Then let your tragedy be enacted here," she told them. "Thus send forth your petition and let them read it by the red blare of destruction." The petition had been sent forth, but the tragedy had only just begun.