.jpg) The

evolution of radical thought and action during the 1870s and 1880s

was an international development, and Chicago was one of its capitals.

The small but vocal group of leaders of this movement convened on several

occasions in Europe and America through the early 1880s. August Spies

and Albert Parsons were, of course, major figures in the Chicago Social

Revolutionary Congress, which drew twenty-one delegates from fourteen

American cities in October 1881. Spies served as secretary, a responsibility

he assumed again at the much larger and more important congress two years

later in Pittsburgh. He and Parsons helped produce the "Pittsburgh Manifesto,"

the statement of principles that they hoped would help galvanize their

cause. The first of its six resolutions called for the "Destruction of

the existing class rule, by all means, i.e., by energetic, relentless,

revolutionary and international action." Three years later the prosecution

offered this document in the Haymarket trial as People's Exhibit 19.

The

evolution of radical thought and action during the 1870s and 1880s

was an international development, and Chicago was one of its capitals.

The small but vocal group of leaders of this movement convened on several

occasions in Europe and America through the early 1880s. August Spies

and Albert Parsons were, of course, major figures in the Chicago Social

Revolutionary Congress, which drew twenty-one delegates from fourteen

American cities in October 1881. Spies served as secretary, a responsibility

he assumed again at the much larger and more important congress two years

later in Pittsburgh. He and Parsons helped produce the "Pittsburgh Manifesto,"

the statement of principles that they hoped would help galvanize their

cause. The first of its six resolutions called for the "Destruction of

the existing class rule, by all means, i.e., by energetic, relentless,

revolutionary and international action." Three years later the prosecution

offered this document in the Haymarket trial as People's Exhibit 19.

Radicalism in Chicago

The transcripts of the Haymarket

trial jury selection and testimony reveal that many middle-class and native-born

Chicagoans took pride in the fact that they could not define different

schools of  leftist

thought, except to say that these groups were all opposed to "American"

beliefs. But radicals of different stripes—socialists, communists,

and anarchists—debated with each other at length about broad and

fine points of doctrine. They agreed on the principle that capitalism

and the wage system exploited the worker, and that the ownership of the

means of production had to be taken out of private hands and returned

to "the people." Anarchists like Spies and Parsons rejected the idea that

even a socialist or communist government should be given economic and

political control of society, since any kind of hierarchical authority

was inherently oppressive.

leftist

thought, except to say that these groups were all opposed to "American"

beliefs. But radicals of different stripes—socialists, communists,

and anarchists—debated with each other at length about broad and

fine points of doctrine. They agreed on the principle that capitalism

and the wage system exploited the worker, and that the ownership of the

means of production had to be taken out of private hands and returned

to "the people." Anarchists like Spies and Parsons rejected the idea that

even a socialist or communist government should be given economic and

political control of society, since any kind of hierarchical authority

was inherently oppressive.

In their view, the best form of government was no institutionalized government at all. They instead called for the free association of responsible individuals without regulation from above. Spies and Parsons disputed the assertion that anarchism (as well as socialism and communism) were "foreign" imports, even if most radical agitators were born abroad. They contended that anarchism was the most natural, democratic, and "American" political arrangement, invoking the founding fathers (and Thomas Jefferson in particular) as their guiding spirits. They charged that the current regime, marked by suffering and exploitation and held in place by might rather than right, was far more "anarchic" in the negative sense of the word than they were. The chaos of contemporary events, they maintained, proved that capitalism caused disorder. Their alternative social vision promised peace and harmony based on equality, freedom, and justice.

The anarchists were no more unified than any other group, however. While the Pittsburgh Congress was notable for bringing people of disparate outlooks together, the quest for unity was inherently complicated by the philosophical objection of anarchists to centralized directives. Among the thorniest points of internal disagreement was the extent to which they should work with labor unions and for such causes as the eight-hour day. To do so, some contended, would be to accept the wage system and concede the value of permitting organizations such as unions to speak for individuals. Spies and Parsons advocated cooperating with organized labor, not only for practical reasons but also on the principle that unions could help overthrow the current order and provide a basis for a post-revolutionary society. This combination of anarchism and unionism became known as "the Chicago idea."

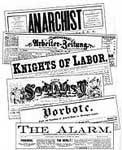

Chicago's anarchist leaders traveled around the Midwest and beyond for meetings, fact-finding trips, and speaking engagements, but they devoted a majority of their efforts to local activities. They harangued both the many and the few at dozens of indoor and outdoor rallies, attended countless political and social gatherings, and managed numerous organs of the radical press. Spies became editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, the leading German-language socialist paper in Chicago, in 1884, the same year Parsons assumed leadership of the Arbeiter-Zeitung's English-language counterpart, The Alarm. Both papers were written and set in type on the upper floors of the Arbeiter-Zeitung building at 107 Fifth Avenue (now Wells Street, just north of Madison) in the heart of the city, close to the offices of the mainstream dailies.

Both men were active in numerous anarchist associations. Parsons was a mainstay of the English-speaking American Group, whose membership included Samuel Fielden, a self-employed teamster who would also be convicted at the Haymarket trial. Spies belonged to the American Group, but was also a central figure in several German-speaking anarchist organizations. Depending on the occasion, he addressed the faithful and the curious in either English or German. Among his associates in the German anarchist community were future Haymarket codefendants Michael Schwab, assistant editor of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, and Oscar Neebe, who owned a small yeast company. Schwab spoke at numerous events, and Neebe helped organize and manage various meetings, parades, and demonstrations.

Anarchism and other schools of socialism had important cultural dimensions in the lives of working-class and immigrant Chicagoans that transcended the sensational sequence of events surrounding Haymarket. Anarchist activities included debates and discussions, picnics, plays, concerts, and parades. Members of radical groups stayed in close touch with political and social developments in Europe, and they held commemorations of such momentous events as the Paris Commune and the democratic uprisings across Europe in 1848.

The Uses of Violence

As the 1880s unfolded, divisions

in the Chicago anarchist community increased. Most Chicago anarchists

identified themselves as members of the International Working People's

Association,

which dated to the Pittsburgh Congress. But by 1885 the more militant

anarchists rejected "the Chicago idea," believing that it compromised

true anarchist principles. Among this group were George Engel, who lived

with his family above a small toy store Engel operated on Milwaukee Avenue,

and printer Adolph Fischer, who had moved to Chicago in 1883, nine years

after Engel, and had become head of the composing room of the Arbeiter-Zeitung.

Dismissing the Arbeiter-Zeitung's editorial policy as too moderate,

they and others founded the Anarchist, which produced four issues

before the police shut it down—at the same time Engel and Fischer

were arrested—following the explosion of the Haymarket bomb. Engel

and Fischer found a like-minded associate in Louis Lingg. Lingg, who was

born in Germany in 1864 and did not come to America until 1885, would

be the youngest of the Haymarket defendants. Engel, the oldest, was fifty-one

when he was hanged in 1887.

Association,

which dated to the Pittsburgh Congress. But by 1885 the more militant

anarchists rejected "the Chicago idea," believing that it compromised

true anarchist principles. Among this group were George Engel, who lived

with his family above a small toy store Engel operated on Milwaukee Avenue,

and printer Adolph Fischer, who had moved to Chicago in 1883, nine years

after Engel, and had become head of the composing room of the Arbeiter-Zeitung.

Dismissing the Arbeiter-Zeitung's editorial policy as too moderate,

they and others founded the Anarchist, which produced four issues

before the police shut it down—at the same time Engel and Fischer

were arrested—following the explosion of the Haymarket bomb. Engel

and Fischer found a like-minded associate in Louis Lingg. Lingg, who was

born in Germany in 1864 and did not come to America until 1885, would

be the youngest of the Haymarket defendants. Engel, the oldest, was fifty-one

when he was hanged in 1887.

The proper role of violence as a tool for revolution consumed the attention of the Chicago anarchists and their enemies, and is obviously of relevance to the Haymarket bombing. In the view of all eight of the anarchists the state put on trial, government and the capitalist owners were merely "force-propped authority." They maintained that although they did not believe in violence for its own sake, armed action in self-defense against this authority was necessary. To adopt such a tactic would be to speak the only language the existing order understood.

Many anarchists were obsessively enthralled with the possibilities of dynamite as an instant equalizer, since it was inexpensive, accessible, portable, and terrifyingly effective. This explosive allowed a single anarchist to carry fearsome destructive power in the pocket of his coat. The threat created by the mere existence of dynamite was in itself a wonderful weapon. "Dynamite is a peace-maker," read an article in the Alarm in April of 1885, "because it makes it unsafe to wrong our fellows." Anarchist rhetoric repeatedly and almost mystically invoked the primordial power of dynamite. Their reverence for it in speech and print was the major evidence used against the defendants at the Haymarket trial.

Especially damning was People's

Exhibit 15, a translation of Revolutionary War Science, published

in 1885 by Johann Most and both advertised in anarchist papers and sold

at some of their gatherings. Most was a well-known and widely feared figure

in  radical

politics in Europe before arriving in 1882 in the United States, where

he lived amidst controversy and persecution until his death twenty-five

years later. Most resided in New York but he made a few visits to Chicago

and was the main author of the Pittsburgh Manifesto. The most notable

and chilling quality of Revolutionary War Science was the matter-of-fact

tone in which it surveyed the different weapons (including bombs of multiple

varieties) available to the dedicated political terrorist, providing step-by-step

instructions on how to assemble them. Caricatures by influential cartoonists

such as Thomas Nast made Most the model in the public mind of the anarchist

as a shaggy-haired, unwashed, wild-eyed, bomb-thrower, alien not only

to America but also to all things decent, rational, and humane.

radical

politics in Europe before arriving in 1882 in the United States, where

he lived amidst controversy and persecution until his death twenty-five

years later. Most resided in New York but he made a few visits to Chicago

and was the main author of the Pittsburgh Manifesto. The most notable

and chilling quality of Revolutionary War Science was the matter-of-fact

tone in which it surveyed the different weapons (including bombs of multiple

varieties) available to the dedicated political terrorist, providing step-by-step

instructions on how to assemble them. Caricatures by influential cartoonists

such as Thomas Nast made Most the model in the public mind of the anarchist

as a shaggy-haired, unwashed, wild-eyed, bomb-thrower, alien not only

to America but also to all things decent, rational, and humane.

How much individual anarchists were actually committed to the use of dynamite in street warfare, and how much it was part of a rhetorical style with which they hoped to inflame their supporters, frighten their enemies, and inspire themselves, is hard to tell. But there is no question that bomb-talking dominated their expression, and that both the anarchists and those they opposed viewed the deployment of dynamite and other deadly devices as a very real possibility, especially in the light of the assassination by bomb of Russian Czar Alexander II in 1881 and other violent assaults on authority. The police and the public credited rumors of bombs being set by the homes of the rich and powerful, and State's Attorney Julius Grinnell brandished correspondence between Spies and Most in front of the Haymarket jury as proof of the former's murderous intentions.

A Series of Confrontations

In the mid-1880s, the country seemed to lurch irresistibly through a series of angry confrontations toward a major blowup, as even thoughtful citizens believed that they were incapable of doing anything but wait for full-scale class warfare to break out. The anarchists repeatedly took to the streets in demonstrations intended to announce their cause and dramatize their presence in the city. They chose Thanksgiving of 1884, for example, to point out that want rather than plenty was the worker's lot. A few thousand demonstrators assembled downtown in a cold rain to hear Parsons, Fielden, Spies, and Schwab address them. They then paraded past the homes of the wealthy. When they repeated this demonstration a year later, the militia was watching.

In April 1885 the anarchists organized a protest rally and parade to counter the festivities surrounding the opening of the new Board of Trade Building at LaSalle and Jackson, the preeminent symbol of the capitalist system they opposed. They were prevented from approaching the building by officers led by Captain Frederick Ebersold, superintendent of police at the time of the Haymarket meeting, and Lieutenant William Ward, who would give the order for the meeting to disperse seconds before the bomb went off.

On May 4, exactly a year

before Haymarket, anarchists and other labor leaders became irate when

the Illinois militia killed at least  two

striking stoneworkers in the quarry town of Lemont, southwest of the city.

Three months later many Chicago citizens, not just anarchists, were outraged

when the police clubbed innocent bystanders during a strike against the

West Division Railway Company. The chief instigator of the violence was

Captain John Bonfield. In his 1893 pardon of the Haymarket defendants,

Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld would cite Bonfield's conduct as

the likely provocation for the Haymarket bomb.

two

striking stoneworkers in the quarry town of Lemont, southwest of the city.

Three months later many Chicago citizens, not just anarchists, were outraged

when the police clubbed innocent bystanders during a strike against the

West Division Railway Company. The chief instigator of the violence was

Captain John Bonfield. In his 1893 pardon of the Haymarket defendants,

Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld would cite Bonfield's conduct as

the likely provocation for the Haymarket bomb.

Social divisions further intensified through the first half of 1886. Unemployment and union agitation increased, as more workers joined a revived eight-hour movement, endorsing a call for a one-day walkout and demonstrations across the country on Saturday, May 1, 1886. In the preceding weeks, the daily papers were full of news of labor warfare, raising the level of public anxiety. Employers and workers in numerous trades reached agreements, but plans for May 1 demonstrations remained in force. The police and Pinkertons remained on constant alert, journalists and public officials talked ominously about the need to put the necks of agitators in halters, and private citizens purchased guns.

From the point of view of labor, the May 1 labor demonstration was a great success, as hundreds of thousands of workers across trades nationally, and tens of thousands in Chicago, lay down their tools. Among many demonstrations in the city was a parade along Michigan Avenue, with Albert Parsons as one of its leaders. These demonstrations took place without serious incident. But such events would make the anarchist leaders marked men when violence did break out three days later in the Haymarket. The Chicago Mail of May 1 told its readers that any turmoil that lay ahead should be attributed to Parsons and Spies. "Mark them for today," an editorial warned. "Hold them responsible for any trouble that occurs. Make an example of them if trouble does occur."

To the extent that the major Chicago dailies covered the May 1 strike, they did so with an anger and suspicion that blamed the agitation on outside radical organizers who misled workers and betrayed their best interests, which lay in trusting their employers. Yes, some of these employers could show greater understanding and flexibility, but the underlying system of capitalism was sound.

In his remarks before sentencing at the Haymarket trial, as in so many other instances, August Spies angrily protested against this view. "Revolutions are the effect of certain causes and conditions," Spies explained. He contended that the "ruling class" could not stop a movement naturally engendered by its own greed and arrogance, no matter how many police and militia it assembled, Gatling guns it purchased, or gallows it erected. "Here you will tread upon a spark, but there, and there, and behind you and in front of you, and everywhere, flames will blaze up," Spies told his accusers. "It is a subterranean fire. You cannot put it out. The ground is on fire upon which you stand."